Broken Screen: Living With Blindness

Gaia Squarci's photographs convey what it feels like to be visually impaired.

— -- Gaia Squarci, an Italian-born photographer, embarked on a project about blindness while studying in New York.

“I was overdosing on images every day and this made me think of how visual perception and psychology are intertwined and how the lack of one of the senses can affect someone’s relationship to the world,” she said. “And in that period of time my identity was being shaped by the way I saw the world as a photographer and so I started wondering, who would I be if I couldn’t see?”

Starting in 2012, Squarci spent two years photographing and getting to know blind people. The resulting project, “Broken Screen,” conveys her subjects’ experiences with powerful sensory immediacy.

Broken Screen: Living with Blindness

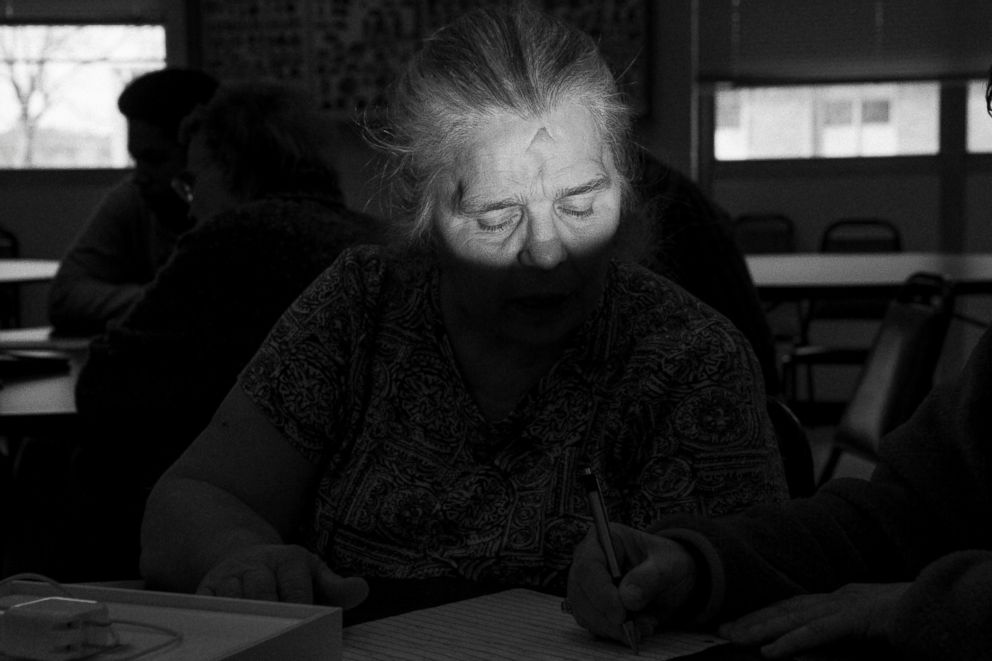

She began the project by visiting Visions in New York, a center that offers courses to visually impaired people. She was led to a photography class taught by a sighted person.

The students "all had vision before, earlier in life, so they had visual memory,” she said. "I started this project thinking I was going to photograph blind people but instead they started taking pictures of me.”

They placed her on a red sofa, put a red hat on her head, put the camera on a tripod, lit her with flashlights, and used long exposure times to make the images. By touching her shoulder and her face, they were able to determine what ended up in the frame. The students are in a collective, called “Seeing with Photography,” and have published a book with Aperture.

She formed a strong bond with one of the students, Dale Layne, who introduced her to other blind people. Layne was born in Guyana, lost his sight when he was 19 and then came to the United States for treatment. His sight had been very fragile since his youth, and he discovered he had glaucoma shortly before losing his sight completely. He described to her how, as a child, he once saw a man in the street with a sign around his neck that read, “Blind Man.”

“He told me this made him feel fear and he just wanted to get away from him,” said Squarci. “He never thought the condition would apply to him later in life. I think Dale at that time gave a candid look at how society looks at blind people. What makes it hard to accept blindness when it comes is that we find ourselves on the other side of the wall that we have built, but it doesn’t necessarily need to be there.”

“When you’re losing sight, the world starts to appear fragmented, like through a broken screen. Then you stop understanding where light comes from,” Layne told Squarci.

Squarci observed that the reality of blindness, which can frighten some, contrasts with its portrayal in literature and mythology as a mysterious and even otherworldly quality. The Portuguese author José Saramago writes in his novel, “Blindness,” about a woman who is the only sighted person among many blind people in a bleak world. He highlights the mysterious and lyrical qualities of blindness while suggesting that it is a universal condition: "[S]he serenely wished that she, too, could turn blind, penetrate the visible skin of things and pass to their inner side, to their dazzling and irremediable blindness.”

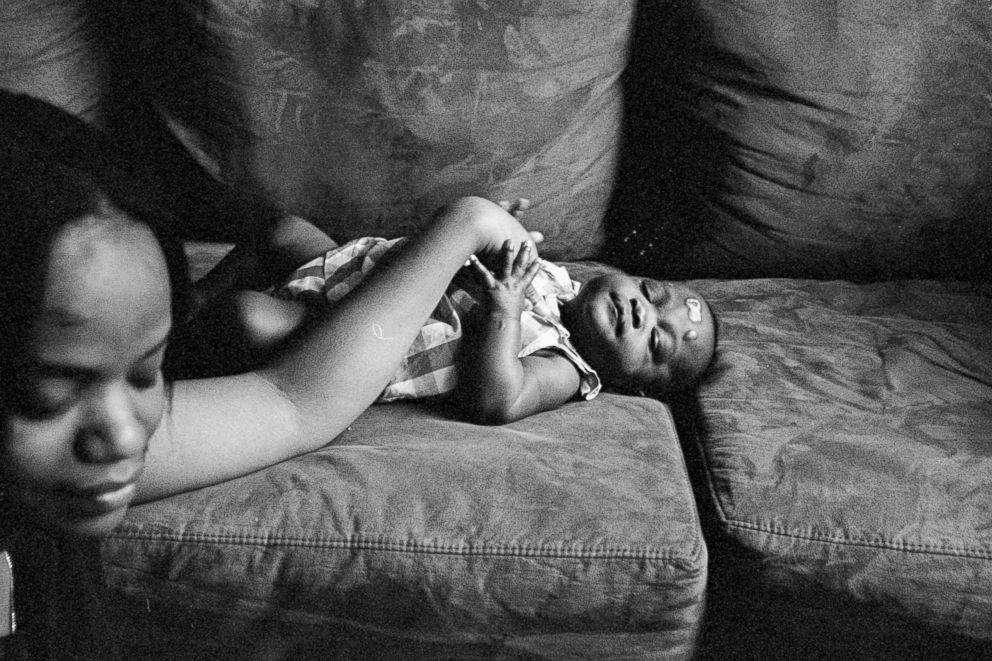

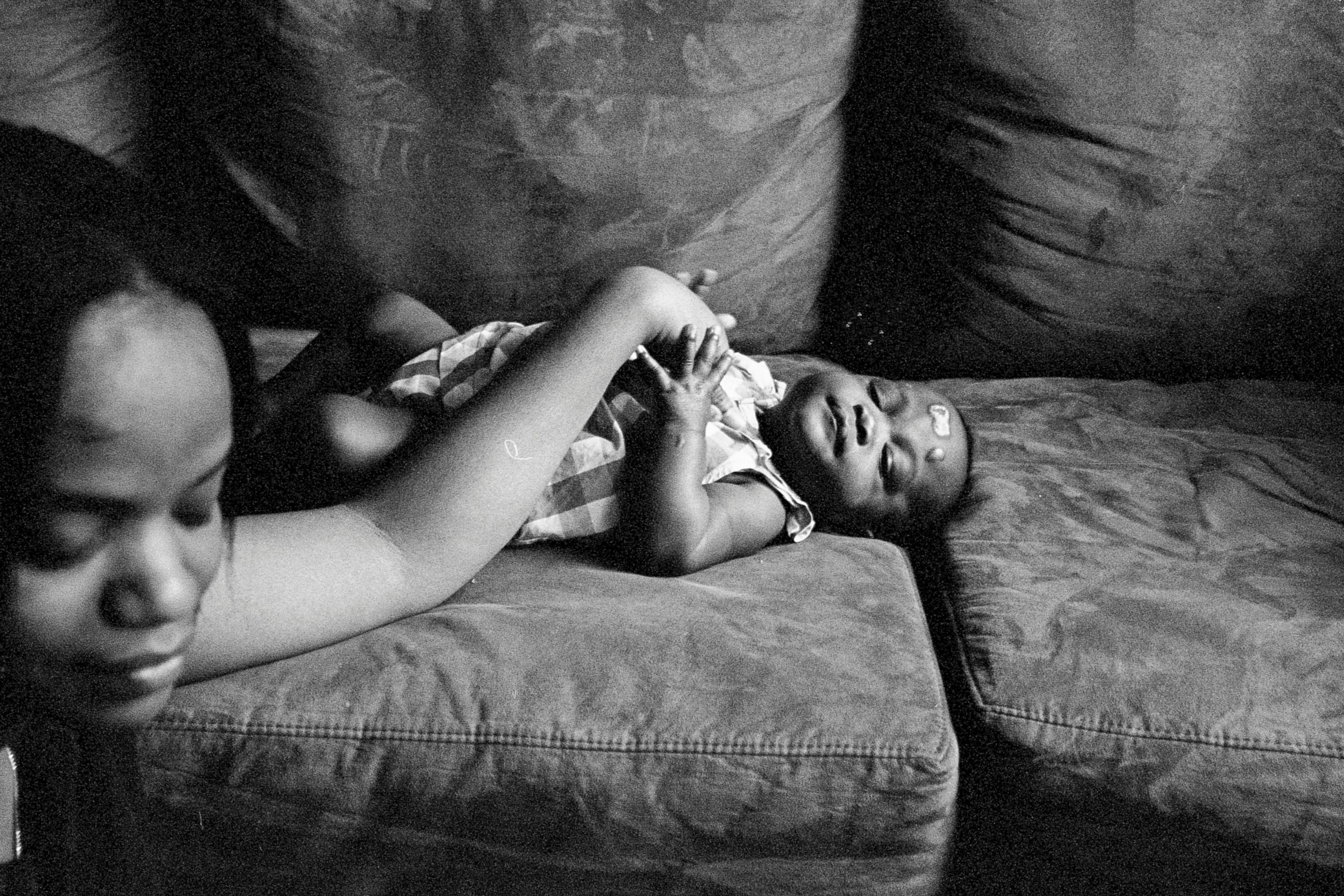

Squarci’s photos, rather than presenting blind people’s experiences as monolithic, elucidate individual moments and feelings, whether it is the love a mother feels for her child, the sensation of being underwater, or the warmth of the sun on your skin.

“Rather than constructing linear narratives, I worked on themes ... about work, identity, what facilities are offered to blind people at museums, the relationship within a couple and between parents and their kids,” she said.

The challenges that blind people encounter range from the professional to the personal --how to get a job, how to be heard in a world which overlooks the blind. Alexandra Hobbes, one of Squarci’s subjects, who went blind at the age of 4, related an experience that she had in a hospital while giving birth.

“She was telling me that it was very hard to be heard as a blind person because ... people didn’t know how to interact with her. The nurses would ask questions of her husband ... who is [also] visually impaired if she was present because they didn’t know how to deal with her. She kept saying I can hear, why don’t you talk to me?”

After the baby was born prematurely, she was placed in an incubator, said Squarci. “I tried to imagine a woman who carried her child in the womb for 9 months and then all of a sudden couldn’t see her or touch her and no one is talking to her in the hospital. That’s her nightmare that she shared with me,” she said.

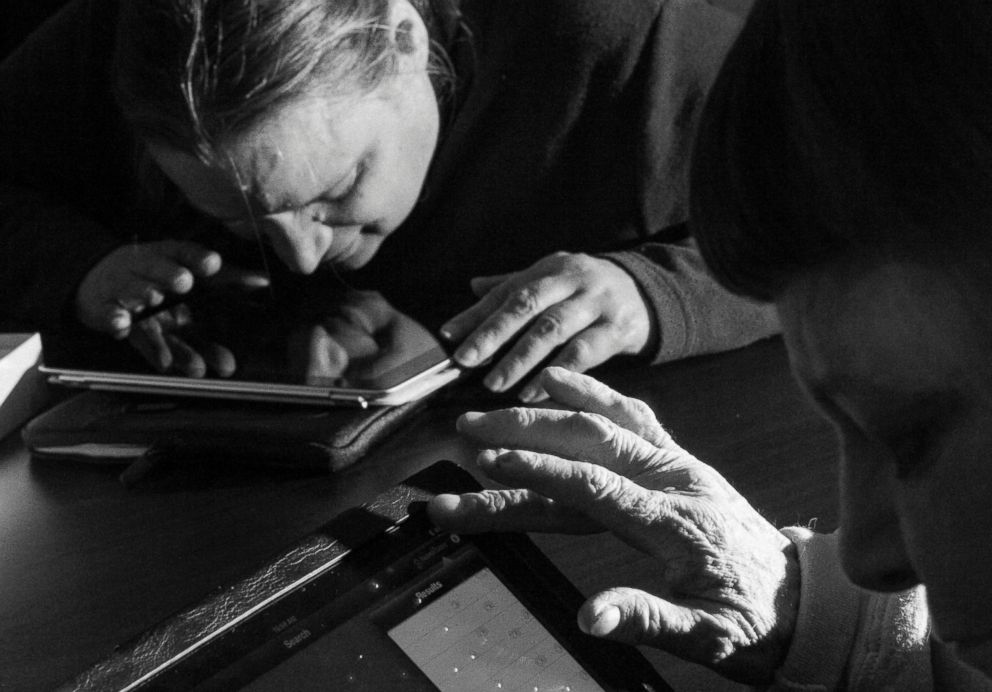

As she worked on the project, Squarci began to understand that people who become blind are forced to reinvent themselves in a society that tends to keep them at a distance.

“All of a sudden, you are this other person that you have to get to know and to accept. I think that losing sight is very humbling, you learn to let go of your pride and you have to give up a lot of your privacy and accept people’s help,” Squarci said. “People deal with it very bravely.”

Squarci said her subjects were eager to communicate that they had learned to accept blindness as part of their lives.

Donald Baker, a radio deejay who is blind, told Squarci: “What I don’t like is sympathy. Don’t walk on eggshells when you talk to me. Don’t be afraid to joke with me and don’t worry about the word ‘Blind.’”

What sets Squarci’s work apart from other photographers who have delved into the world of disabilities, such as Diane Arbus, is her ability to convey to her viewers what it feels like to be blind. There is no sense of otherness -- when you look at her pictures, you feel you are the person in the picture. The diffused light, the murky shadows, the feeling of navigating the world through sound and touch permeate the images.

"{I wanted] to dive into their skin ... and it was all about the person I had in front of me and what questions he or she awakened in my mind. My role with photos was to address those questions and not to give an answer on their behalf," Squarci said.