Suspected Terror Attack at OSU Launched Nationwide Dragnet for Information

A young analyst found what may be the biggest piece of evidence in the case.

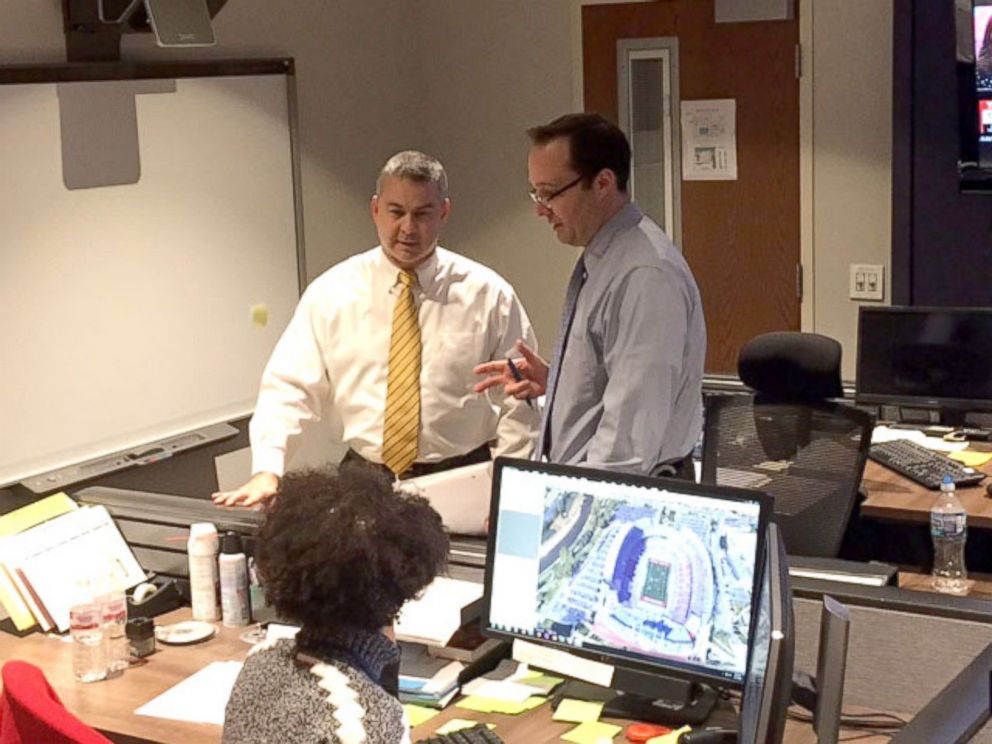

— -- Brian Quinn was having a routine morning chat with a highway patrolman on Nov. 28 when one of his staffers interrupted: “Gentlemen, you need to know of a developing situation.”

“There’s been a police shooting on the [Ohio State University] campus involving a car versus a crowd,” the staffer told Quinn, who runs the Ohio Strategic Analysis and Information Center in Columbus.

It was the start of a nationwide dragnet for information.

“We don’t know where the shoe may be falling next,” said Mike Hartzler, another senior homeland security official in Ohio.

It’s a tough question to answer quickly, especially with new technologies allowing criminals and terrorists to increasingly operate in secret. So local authorities have developed a network of “fusion centers” in states and cities across the country, all looking to help each other compile, vet and swap information related to threats in their areas.

“There’s no nation on this planet that has this capability right now,” said Mike Sena, president of the National Fusion Center Association, which represents and promotes the 78 fusion centers across the country.

But what does this capability really look like, and why is such information-sharing so important? The OSU incident offers a glimpse.

“TAKE A LOOK AT THIS”

At 9:53 a.m. on Nov. 28, OSU police officer Alan Horujko fatally shot the man who had just driven a car into several people and slashed bystanders with a knife.

Soon after – while law enforcement officers from 28 different agencies were still trying to secure the area and help victims – authorities picked up a driver’s license with the name of a possible suspect: Abdul Razaq Ali Artan.

The name was sent to Quinn’s fusion center. Within minutes, a young female analyst uncovered what may be one of the most important pieces of evidence in the case.

“I think I found something. Take a look at this,” Quinn recalled the analyst calmly telling him.

She had somehow found Artan’s Facebook page, even though it was under the name “Abdi Razaq.”

She could see he left behind a digital diatribe against U.S. foreign policy, declaring in his final post, “If you want us Muslims to stop carrying [out] lone wolf attacks, then make peace with [ISIS].”

The analyst forwarded the Facebook page to other fusion centers in Ohio and pushed it to federal partners, including the Joint Terrorism Task Force, or JTTF, in Columbus, where FBI agents, city police officers and others sit side-by-side to investigate federal terrorism cases.

Hartzler, director of the Greater Cincinnati Fusion Center, responded to the analyst’s email with a simple message: “Great work.”

His own analysts in Cincinnati had jumped in to help their counterparts 100 miles away.

In years past, when fusion centers weren’t as readily able to help in the middle of a crisis, finding a Facebook account like that “would have been done hours later,” according to Quinn. “Nowadays we’re able to get that information while officers are still on the scene.”

“THE DETAILS DO MATTER”

Shortly after 11 a.m., reports online and then on cable news erroneously began to say Artan used a machete to slash some of his victims. In fact, Artan had used a butcher knife.

That may seem like a minor difference, but law enforcement officials worried the false reporting could have serious consequences.

In those minutes and hours after an attack, authorities scramble to determine whether there may a bigger plot, and they look to see if similar attacks are underway elsewhere.

So “whether it’s a knife or a machete or a sword or a gun all matter to those who are investigating,” according to Rick Zwayer, executive director of homeland security for the state of Ohio.

In addition, if investigators on the ground falsely hear there was a machete used, they may waste precious time looking for a weapon that never existed, officials said.

State and local officials relied on a fusion-center database known as “SitRoom” to correct the rumors and “misinformation,” as Quinn put it. They also used the database to provide situational updates, including the latest on whether other people were involved in the attack and the status of those who were injured.

“The details do matter,” Zwayer insisted.

AN EMERGING PICTURE

By early Monday afternoon, authorities had pieced together a preliminary picture of the attack and the suspect.

“The people who should have been talking to each other were talking to each other,” said Deputy Chief Michael Woods, the head of the Columbus Police Department’s Homeland Security Division, who had raced to the scene at OSU.

It turned out Artan recently enrolled at the school, coming to the United States two years ago after fleeing war-torn Somalia and living in a refugee camp in Pakistan. Officials were keenly aware that only weeks earlier, ISIS had issued an online magazine urging Muslims to “crush” Westerners with vehicles and then attack those still standing with firearms or knives -- a call for bloodshed eerily like the incident that had occurred just hours earlier.

At 11:29 a.m., the FBI issued a “situational news notification” to personnel throughout the agency, indicating that the FBI’s Counterterrorism Division in Washington was getting more involved in the case.

The JTTF in Columbus would begin to take on a more prominent role, too. After all, JTTFs are investigators who “deal with the classified side of things,” while fusion centers act more like researchers and messengers, according to one JTTF member outside of Columbus.

When an attacker might be on the move, the “JTTF isn’t where you want to send real-time info about what car the suspect is driving” or where the suspect may be heading next, the JTTF member said. “That’s more of the fusion center role.”

Around 1 p.m., a staffer at one of the Ohio fusion centers typed Artan’s full name into the “SitRoom” database, hoping agencies in other cities and states would see it and check their own records for leads. Not a single fusion center, however, responded with more information.

Artan had flown under the radar. He didn’t come up in FBI files either, and authorities were becoming increasingly convinced that he didn’t have any accomplices.

Federal officials began to shift their concerns to something else: copycats.

A NATIONWIDE CONFERENCE CALL

At 3 p.m. on Nov. 29 – the day after Artan’s assault – senior U.S. officials held a half-hour conference call with thousands of federal, state and local law enforcement personnel across the country, updating them on the investigation and stressing vigilance.

Artan was undoubtedly inspired by Al Qaeda and ISIS propaganda, FBI Deputy Assistant Director Steve Hersem told those on the line, according to one official who was listening to the call.

“This is another unfortunate example of what we’ve been talking about for the past year and a half,” said FBI Assistant Director Kerry Sleeper, the head of the FBI’s Office of Partner Engagement, according to a second official on the call.

“Make sure that any suspicious activity threats are reported immediately” to JTTFs or fusion centers, and make sure “you are appropriately monitoring social media” for calls to violence, the FBI officials stressed to those listening, sources said.

According to one source, Sleeper concluded with this thought: “Unfortunately with the holidays coming, we’re probably going to be talking again in the near future.”

Through an FBI spokesman, FBI officials in Ohio and JTTF members in Columbus declined to be interviewed for this article.