NYC Doctor, Who Survived Ebola, Says Experimental Vaccine Could Be 'A Way Forward'

Craig Spencer was diagnosed with Ebola last year.

— -- A New York City doctor, who made headlines after he was diagnosed with Ebola, said he hoped an experimental vaccine could be “a way forward” for a region decimated by the deadly virus.

Craig Spencer, an emergency room physician at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center, made headlines last year when he contracted Ebola after treating patients for the disease in Guinea. His diagnosis in New York City set off a wave of media coverage of the 33-year-old doctor who spent 20 days in isolation as he fought off the deadly disease.

After his treatment Spencer returned to Guinea to treat patients and he got to see firsthand how the vaccine trial affected patients and health care workers.

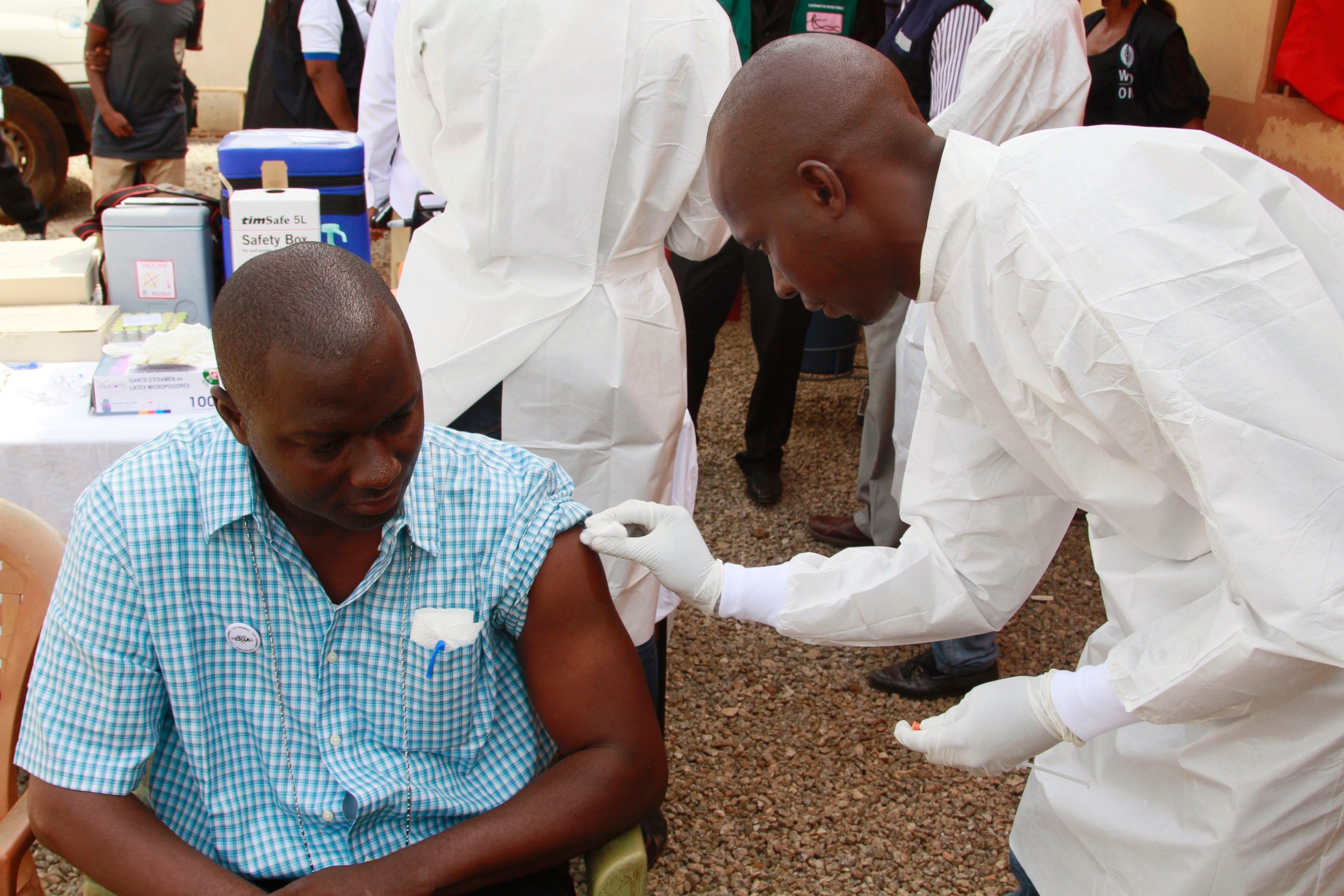

In a newly published study in the medical journal The Lancet, researchers found that an experimental Ebola vaccine appeared to be successful in early trials. Thousands of patients who had been exposed to Ebola were given the vaccine right away or after three weeks. Those given the vaccine right way were found not to develop the virus, although researchers started tracking virus results after 10 days in case anyone who had already been infected. Sixteen of those who were given the vaccine after 21 days developed the virus.

Officials from the World Health Organization said more research would be needed to confirm the early findings from the Guinea-based study.

"If proven effective, this is going to be a game-changer," Dr. Margaret Chan, director-general of the World Health Organization, which sponsored the study, told the Associated Press. "It will change the management of the current outbreak and future outbreaks."

Spencer said it was difficult for health workers to get the trial underway — many in the country were still afraid of health care workers or heard rumors about the government not helping patients in need.

“When I was back, it certainly was not calm, it was not easy,” said Spencer. “Many people were still very uncomfortable with Ebola in the country.”

After seeing the devastation of the disease with no clear treatment or vaccine, he said the vaccine is “certainly helpful,” but remains concerned people will assume it can end the outbreak alone.

He pointed out the outbreak had decimated the medical infrastructure in the countries hit hard by Ebola leading to deaths by other more common illnesses or complications like childbirth.

More people “could die of measles than will die of Ebola throughout this outbreak,” explained Spencer, citing that an outbreak of measles could cause up to 200,000 cases due to under vaccination.

“There was a study that estimated that up to 7 percent of doctors in Sierra Leone and 8 percent in Liberia,” had died from Ebola, said Spencer. “This was for a region that before the outbreak had less practicing doctors [in] countries combined that there were in the one hospital in New York City where I was treated.”

He remained concerned that if people think the vaccine works they will no longer think help is needed, even though measles—which can be prevented with a vaccine—also kills far more than Ebola.

“One of the big messages is that Ebola is bad but post-Ebola could be worse,” said Spencer.

Spencer said he's gone to Africa for years and expects he’ll be back in west Africa in the next year to work with patients.

“I’ve learned so much about medicine and humanity," Spencer said. "What it really comes down to is everyone deserve the same right to be treated and to be free of disease.” said Spencer.